Introduction

Cost‐effectiveness analyses (CEAs) conducted alongside randomised controlled trials are an important source of information for decision-makers in the process of technology appraisal (Ramsey et al., 2015). The analysis is based on healthcare outcome data and health service use, typically collected at multiple time points and then combined into overall measures of effectiveness and cost. A popular approach to handle missingness is to discard the participants with incomplete observations (complete case analysis or CCA), allowing for derivation of the overall measures based on the completers alone. We note that slightly different definitions of CCA are possible, depending on the form of the model of interest, the type of missingness and the inclusion of observed covariates. This approach, although appealing by its simplicity, has well-recognised limitations including loss of efficiency and an increased risk of bias. We propose the use of linear mixed effects models (LMMs) as an alternative approach under MAR. LMMs are commonly used for the modelling of dependent data (e.g. repeated-measures) and belong to the general class of likelihood-based methods. LMMs appear surprisingly uncommon for the analysis of repeated measures in trial-based CEA, perhaps because of a lack of awareness or familiarity with fitting LMMs.

Methods

Linear mixed model extends the usual linear model framework by the addition of “random effect” terms, which can take into account the dependence between observations.

\[ Y_{ij}=\beta_1+\beta_2 X_{i1}+\ldots+\beta_(P+1) X_{iP}+\omega_i+\epsilon_{ij}, \]

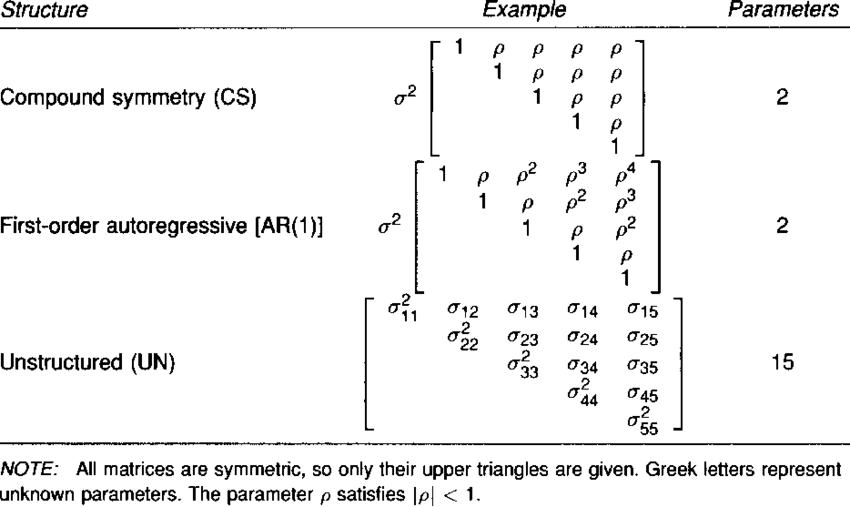

where $Y_{ij}$ denotes the outcome repeatedly collected for each individual $i=1,\ldots,N$ at multiple times $j=1,\ldots,J$. The model parameters commonly referred to as fixed effects include an intercept $\beta_1$ and the coefficients $(\beta_2,\ldots,\beta_{(P+1)})$ associated with the predictors $X_{i1},\ldots,X_{iP}$, while $\omega_i$ and $\epsilon_{ij}$ are two random terms: $\epsilon_{ij}$ is the usual error term and $\omega_i$ is a random intercept which captures variation in outcomes between individuals. The models can be extended to deal with more complex structures, for example by allowing the effect of the covariates to vary across individuals (random slope) or a different covariance structure of the errors. LMMs can be fitted even if some outcome data are missing and provide correct inferences under MAR.

A particular type of LMMs commonly used in the analysis of repeated measures in clinical trials is referred to as Mixed Model for Repeated Measurement (MMRM). The model includes a categorical effect for time, an interaction between time and treatment arm, and allows errors to have different variance and correlation over time (i.e. unstructured covariance structure).

Incremental (between-group) or marginal (within-group) estimates for aggregated outcomes over the trial period, such as quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) or total costs can be retrieved as linear combinations of the parameter estimates from Equation 2. For example, the mean difference in total cost is obtained by summing up the estimated differences at each follow-up point, while differences on a QALY scale can be obtained as weighted linear combinations of the coefficient estimates of the utility model.

Conclusions

We believe LMMs represent an alternative approach which can overcome some of these limitations.

First, practitioners may be more comfortable with the standard regression framework.

Second, LMMs can be tailored to address other data features (e.g. cluster-randomised trials or non-normal distribution) while also easily combined with bootstrapping.

Third, LMMs do not rely on imputation, and results are therefore deterministic and easily reproducible, whereas the Monte Carlo error associated with multiple imputation may cause results to vary from one imputation to another, unless the number of imputations is sufficiently large.

Although the methodology illustrated is already known, particularly in the area of statistical analyses, to our knowledge LMMs have rarely been applied to health economic data collected alongside randomised trials. We believe the proposed methods is preferable to a complete-case analysis when CEA data are incomplete, and that it can offer an interesting alternative to imputation methods.